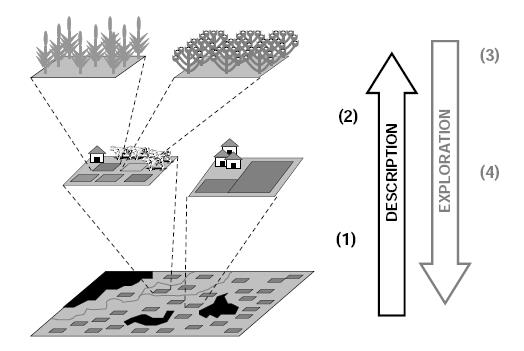

Abstract

Increasing agricultural production and preventing further losses in biodiversity are both legitimate objectives, but they compete strongly in the developing world.In this study, current tensions between agricultural production and environmental conservation were described and analysed in Mbire District, an agricultural frontier shared with wildlife that lies in the Mid-Zambezi Valley, in the northern fringe of Zimbabwe. The potential of conservation agriculture (CA) to intensify agricultural production with minimum negative environmental effects was then explored. The population of Mbire District almost doubled between 1992 and 2002, while the livestock densities increased at rates above 15% in the early 1990s and the late 2000s. From 1980 to 2007, the expansion of farmland over the years was described by an exponential relationship. It was suggested that these changes affected elephant and buffalo numbers negatively. Increase in human population, increase in cattle population, and expansion of cotton farming were all drivers on the observed land use change. However, cotton farming was demonstrated to be paramount, enabling cattle accumulation and expansion of plough-based agriculture. The ‘environmental footprint’ per farm was increasing significantly with the area under cotton and with the number of draught animals owned. A kilogram of seed cotton required 50% more land, removed twice as much N, 50% more K and 20% more P than a kilogram of cereal. However, except for pesticide, one man-day invested in cotton production had a smaller environmental footprint than a man-day invested in cereal production. As farming in Mbire District is limited by labour more than by land, specialising in cereal production would increase the total area occupied by crops and fallows, whilst specializing in cotton production would reduce this area. Therefore, maintaining or increasing the relative profitability of cotton vs. cereal may ‘spare land’ for nature. Compared with current farmers' cropping practices (CP), CA had no effect on cotton productivity during years that received average or above average rainfall. During a drier year, however, CA was found to have a slightly negative effect (110 kg ha-1 less in on-farm trials and 220 kg ha-1 less in farmers' cotton fields). Most soils in the study area are coarse-textured soils, on which runoff were significantly greater with CA than with CP. For these reasons, farmers perceived ploughing as necessary during drier years to maximize water infiltration, but saw CA as beneficial during wetter years as a means to ‘shed water’ and avoid waterlogging. In Zimbabwe, the approach used in the extension of CA appears to differ little from an earlier attempt to intensify smallholder agricultural production almost a century earlier: the Alvord model. In particular, the rationale of African smallholder farming has been persistently ignored. The analysis of smallholder farming practices in Mbire District showed how the socio-economic constraints they faced predisposed them towards extensification. In particular, labour availability for weeding was found to be a major limiting factor in the area. The increased weed pressure in CA is therefore a major reason preventing smallholders from embracing it. As a conclusion, mitigating conflicts between agricultural production and biodiversity conservation will require major innovations, far beyond CA. CA should be seen as part of a larger basket of technologies aiming at ‘ecological intensification’. In parallel to the development of technical innovations, local institutions should be empowered and strong regulations put in place.